Bearing the Weight of Love

Let go of stoicism and sentimentality, practice lament and amazement

Welcome to my Lenten Saturday series, Love & Unlove in Lent. You can read previous entries here: Week 1

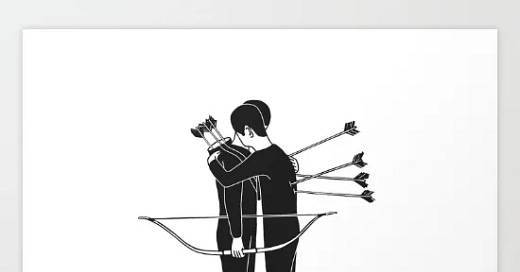

Love bears up under anything and everything that comes.

—1 Corinthians 13:7 (AMPCE)

We heard poet Christian Wiman read at an event in Manhattan a few years ago. Wiman, who was diagnosed at age 39 with a rare and incurable form of lymphoma, described his experience of dodging the prescriptions offered by Christians trying to make him feel better about the five years he had been given to live. Wiman said something that Brian frequently reminds me of when our occasionally awkward efforts to love others go awry: “Proclamation outside of loving is like having a conversation with someone using a megaphone.” 1

In the nineteenth century, Danish poet-philosopher-theologian Søren Kierkegaard, thought a lot about Christian love. When I heard Christian Wiman’s story, it brought this to mind:

Love is not what you try to do to transform the other person or what you do to compel love to come forth in him; it is rather how you compel yourself. Only the person who lacks love imagines himself able to build up love by compelling the other.

The one who truly loves always believes that love is present; precisely in this way he builds up. In this way he only entices forth the good; he ‘loves up’ love; he builds up what is already there. For love can and will be treated in only one way—by being loved forth.— Søren Kierkegaard

As well-meaning people tried to compel love from the man living with a terminal illness, their declarations of faith sounded like a megaphone to his sore ears. Often, this is how it happens: the words and gestures we use to express compassion are drowned out by the noise of our own fear that God’s love won’t survive the suffering in this world. Additionally, our diluted definitions of love, and the ideologies we create to try to compel and coerce love from others cause us to shout our love at one another in slogans and then exit the room with a rhetorical mic drop.

As we meditate on love and unlove this Lent, we remember through the life and death of Jesus that he didn’t virtue signal cruciform love, and neither can we. Instead, through our daily practices of embodied agape, we hope to ‘love up love’ in one another.

How can we “love up love”?

Last week, we examined the context of 1 Corinthians through theologian Fleming Rutledge’s commentary that the crucifixion is the “touchstone” of authentic Christian love, giving significance to everything else. Regarding the church at Corinth, she writes:

The Corinthian church is an important test case because that congregation seemed unable to locate itself correctly with regard to the crucifixion. They placed themselves either beyond the cross, as though already raised from the dead…, or above the cross, as though suffering was behind them and beneath them … rather than in the cross. These problems, in Paul’s judgment, were the cause of the Corinthian Christians’ deficiencies with regard to love. That is why he wrote the famous thirteenth chapter of 1 Corinthians…

— Fleming Rutledge, The Crucifixion: Understanding the Death of Jesus Christ

Rutledge views Golgotha, rather than a wedding ceremony, as the ideal setting for the Apostle Paul’s beautiful poem. When we read 1 Corinthians 13 in light of what it means to witness the “sustained, unconditional agape of Christ exemplified on the cross,” we are invited to deepen our understanding of the love we give and receive each day. This carries specific implications for how we express love for one another, especially towards those who are suffering:

“Sentimental, overly “spiritualized” love is not capable of the sustained, unconditional agape of Christ shown on the cross. Only from the perspective of the crucifixion can the true nature of Christian love be seen, over against all that the world calls “love.” The one thing needful, according to Paul, is that the Christian community should position itself rightly, at the juncture where the cross calls all present arrangements into question with a corresponding call for endurance and faith.”

— Fleming Rutledge, The Crucifixion: Understanding the Death of Jesus Christ

This week and next, let's explore together two common misinterpretations of agape love that have been seen as warm gestures but fall short of the deeper meaning of Christian love. I hope to help us imagine the genuine expressions of this love and engage in a small, meaningful practice that, with God’s guidance and a sprinkle of our own lightheartedness, will strengthen our capacity for love that bears all things.

Bearing the weight of love by letting go of stoicism and sentimentality and practicing lament and amazement

While suffering and grief are intrinsic to the human experience, our ability to express sorrow has diminished in a world that often swings between sentimentality and stoicism. Reflecting on the past few years, it's impossible to ignore the collective pain of war, racial injustice, economic fallout, mass murders, and political vitriol—all contributing to a profound need for lament, a way to acknowledge and articulate our sorrow. Yet, without guidance, many find expressing this deep sadness can feel as complex as trying to speak a foreign language like Latin. Phrases such as “sending thoughts and prayers” often feel inadequate, even trivial, leaving us wondering which words and actions might help ease our grief. If there was once a shared understanding of how to lament, how can we find our way back to that language?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Restful to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.